One day, in my spare time, I will write about famous royal women in history. Until then, I will content myself with Anne Thériault’s Queens of Infamy series over on Longreads (which you should be reading). And as a part of that series, I will make an exception for non-royal Gertrude Bell, an Englishwoman who was instrumental in getting the British out of the government of the Middle East.

How to summarize Gertrude Bell? She was the daughter of one of Britain’s titans of industry, independently wealthy, full of energy, and an adventurer through and through. Before she explored the Middle East, she climbed the most difficult mountains in the Alps, mostly because she could.

Once she started exploring the Middle East, she became omnivorous about it, learning not only the languages and the customs, but also the history and peoples and more. Many of her expeditions were to ruins and historical sites that she was the first Westerner to explore, and the maps she created were the best of their ilk.

As WWI broke out, she offered her services and knowledge to the British Empire. They eventually took her up on the offer (of course there was sexism and having to prove she deserved to be in the room before anyone would start taking her seriously), and her knowledge of the tribal structures and people in the Middle East was a great asset during the war.

She was also instrumental in setting up Iraq as an independent country after WWI. She fought to get the best structure for the future Iraqis; the British government back in London was all about doing what was easiest for them. Those two things did not often align.

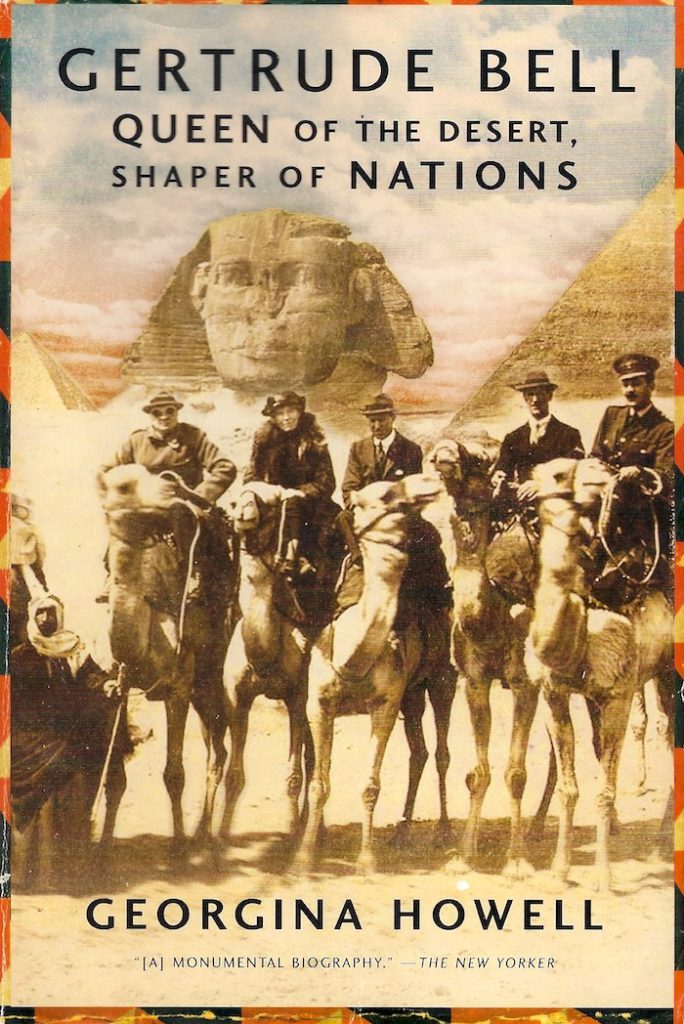

Basically, Gertrude Bell was a force to be reckoned with and historically important. Gertrude Bell, Queen of the Desert, Shaper of Nations was a lovely introduction to her. Recommended.